Meet the American who invented Band-Aids: cotton buyer and devoted husband Earle Dickson

Simply brilliant creation paired cotton with surgical tape, helped treat wife's household nicks and cuts

Earle Dickson invented the Band-Aid in 1921 — here's his remarkable story

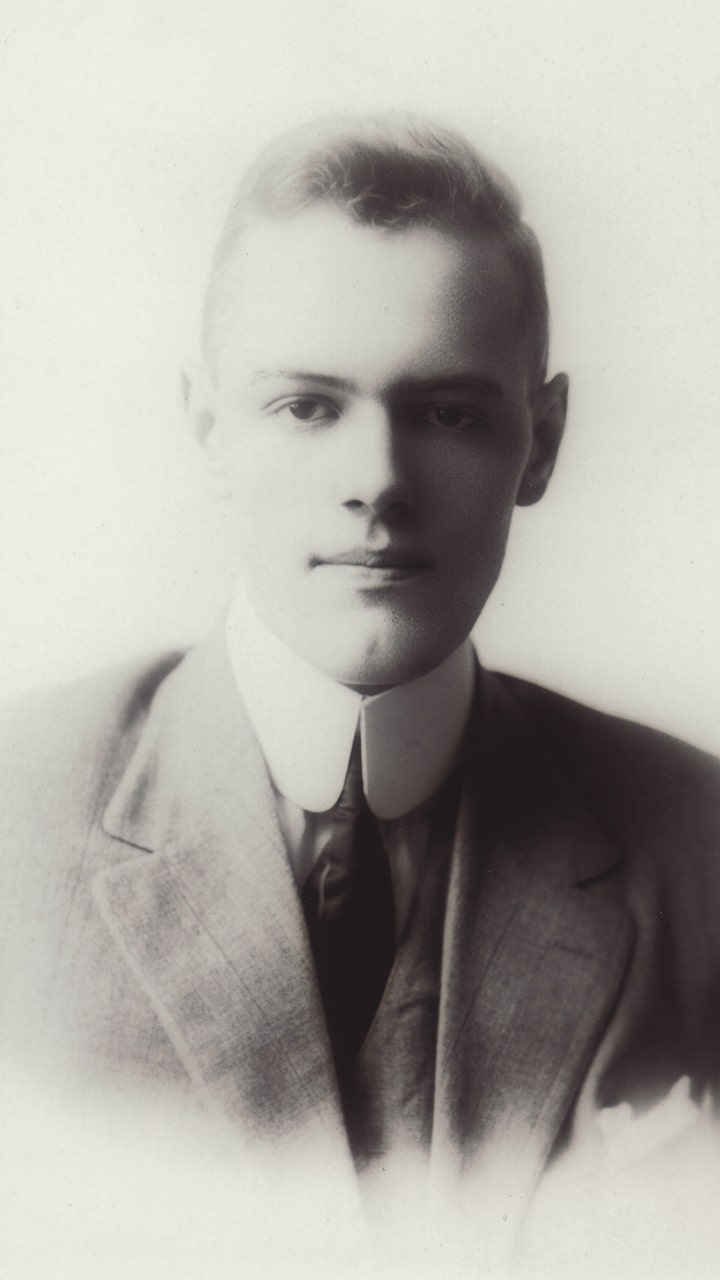

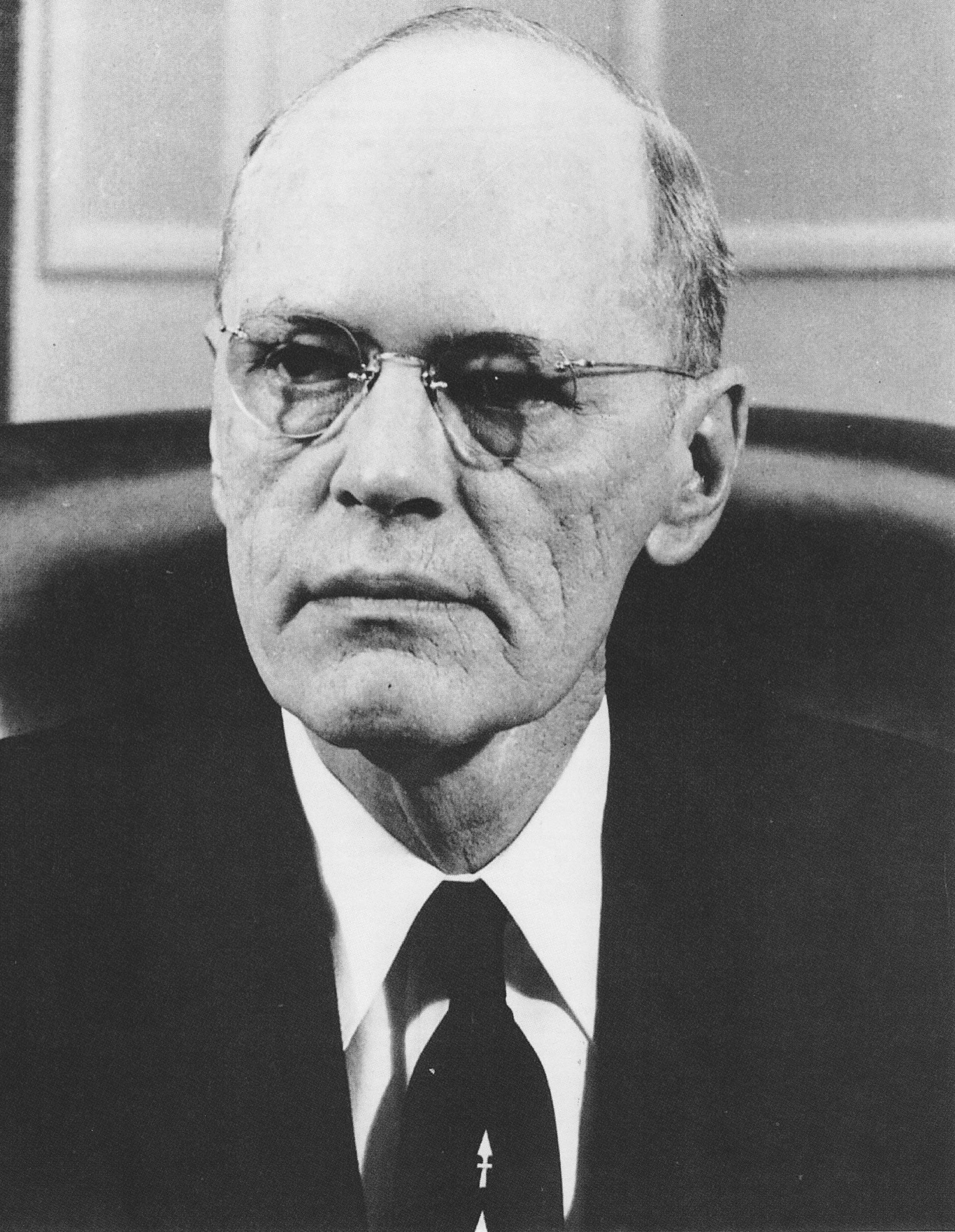

Cotton buyer Earle Dickson, born in Tennessee, created a way to treat common household cuts and scrapes. Band-Aids are now a universally recognized first-aid product.

There is genius in simplicity, which makes the Band-Aid one of the most brilliant inventions in human history. A little adhesive tape, some cotton — and voila! The world is suddenly better.

Band-Aids are so ubiquitous and trusted today that it’s hard to imagine the planet or a medicine cabinet without them.

Yet they are a fairly recent addition to home and professional health care — invented only a century ago by a Johnson & Johnson employee named Earle Dickson.

MEET THE AMERICAN WHO INVENTED THE TV REMOTE CONTROL: SELF-TAUGHT CHICAGO ENGINEER EUGENE POLLEY

He wasn't an inventor. He was a cotton buyer for the New Jersey company. And apparently he was one of the all-time great husbands as well.

"In 1917, Dickson married Josephine Frances Knight," writes the Lemelson-MIT Program, an inventors’ think tank at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

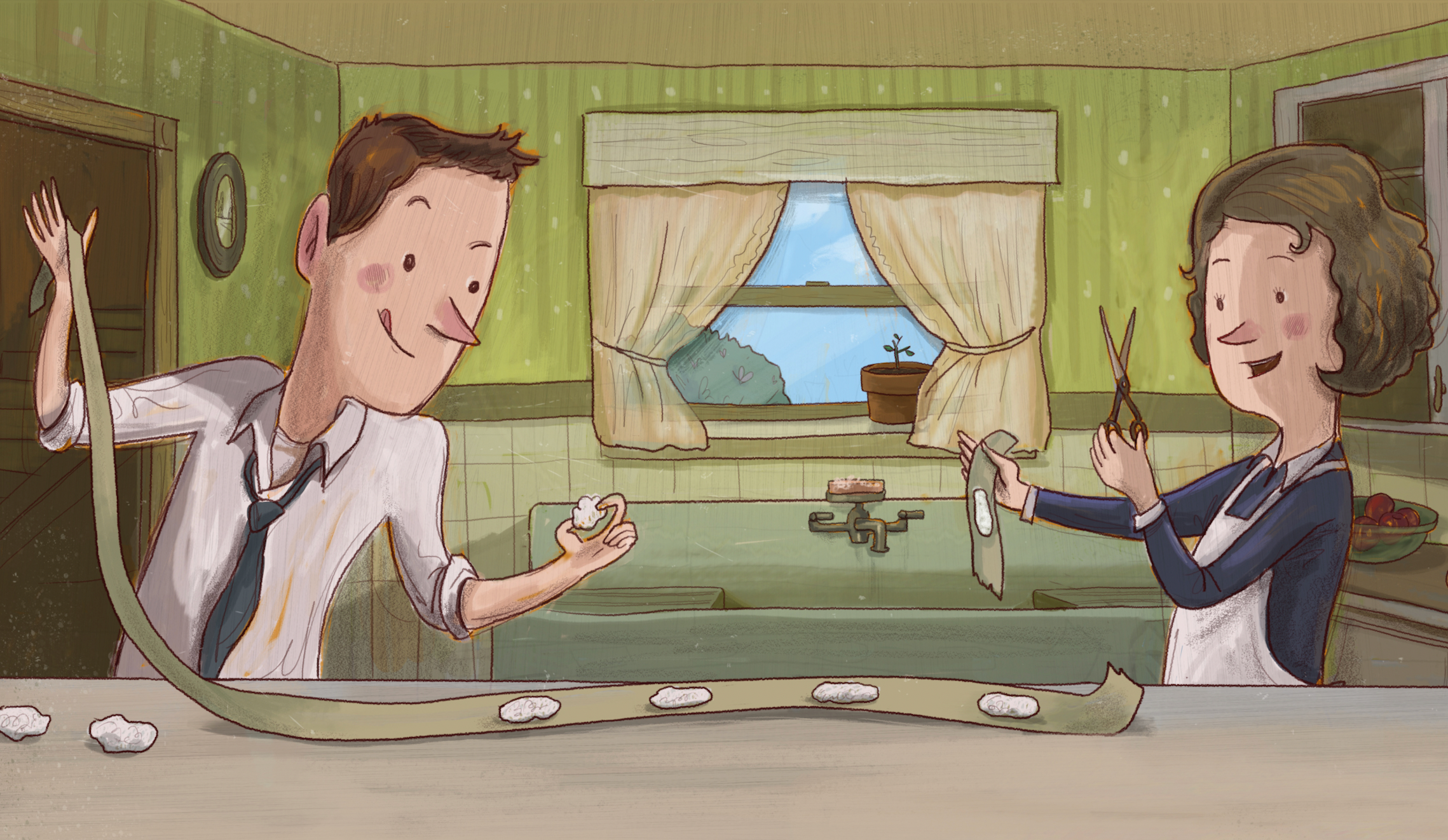

Earle Dickson was a newlywed in about 1920 when he conceived an idea to treat common household nicks and cuts. Johnson & Johnson then introduced his innovation as the Band-Aid in 1921. (Courtesy Johnson & Johnson)

"He quickly realized that his new bride seemed to constantly be nicking her fingers while working in the kitchen, and he thought the big bandages he was using to help her treat them were too large and clumsy."

He found inspiration right there in his own home.

"Earle took two Johnson & Johnson products — adhesive tape and gauze — and combined them to make the first adhesive bandage," writes Johnson & Johnson company historian Margaret Gurowitz.

Band-Aids are a low-tech invention, which makes their recent addition to our lives all the more surprising.

MICRO-PREEMIE BORN ‘ON THE EDGE OF VIABILITY’ IN TEXAS CELEBRATES 1ST BIRTHDAY: ‘QUITE THE SURVIVOR’

Transformative technologies such as the automobile, the miracle of flight and the seemingly impossible feat of transatlantic radio communication were all pioneered two decades or more before the Band-Aid.

Put another way: People could communicate instantly between New York City and London before they could stick a bandage on a bloody finger.

Dickson’s clever effort to comfort his wife would soon have an identity.

Brand-new product

Johnson & Johnson embraced Dickson's idea — and dubbed the product the Band-Aid. The brilliant brand name is credited to factory superintendent W. Johnson Kenyon, according to a report by The Kiplinger Magazine in 1964.

Band-Aids hit the market in 1921, peddled at drugstores by traveling salesmen for Johnson & Johnson.

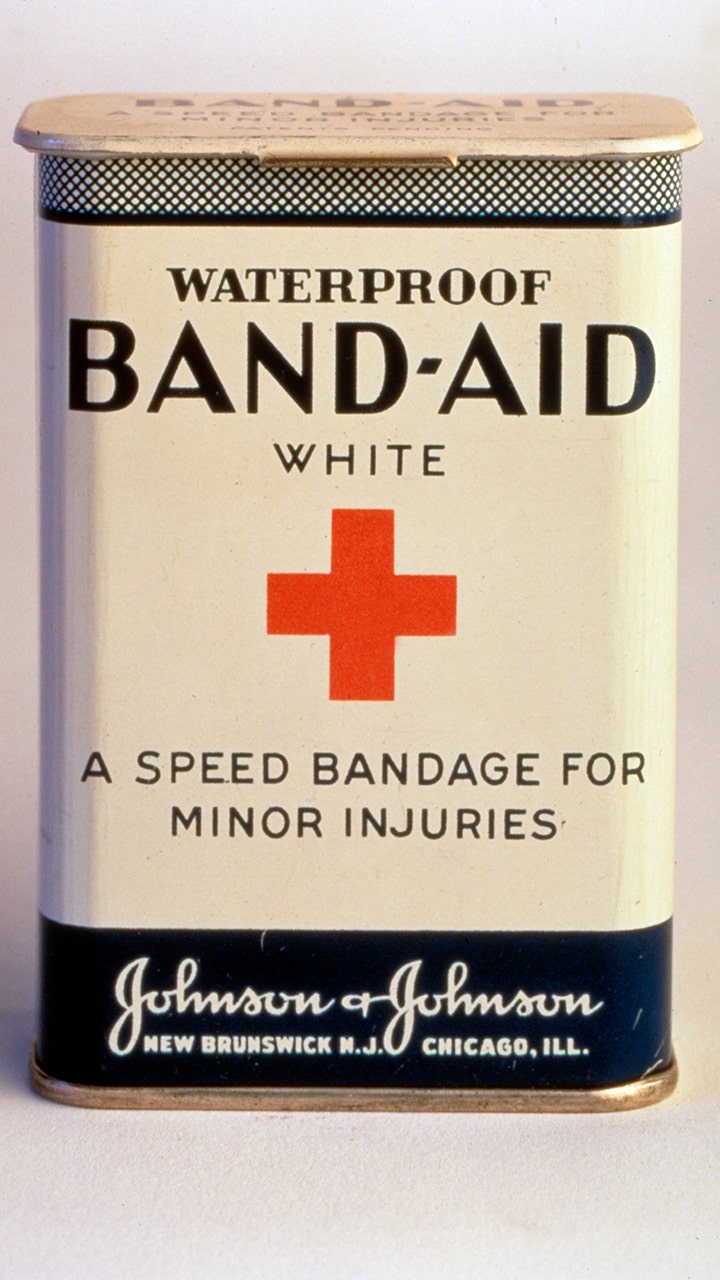

A vintage Johnson & Johnson Band-Aid box. The product was introduced in 1921. (James Keyser/Getty Images)

The generic term is adhesive bandages. Yet North Americans, and other people around the world, know them by the brand name Band-Aids.

In the United Kingdom, adhesive bandages are known generically as plasters; the European equivalent of the Band-Aid is the Elastoplast.

Band-Aids have been such a success that the term is used in everyday conversation in American English in place of adhesive bandages — so that the public sees no distinction between the two.

"His success resulted in the first commercial dressing for small wounds that consumers could apply with ease."

It’s very much the way we refer to tissues as Kleenex or cotton swabs as Q-Tips.

Whatever they’re called, Dickson’s innovation dramatically improved first aid forever.

"Dickson created a prototype of cotton gauze and adhesive strips covered with crinoline that could be peeled off to expose the adhesive, easily allowing the gauze and strip to be wrapped over a cut," writes the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

"His success resulted in the first commercial dressing for small wounds that consumers could apply with ease, and created a market that continues to thrive today."

‘Piece of rag around the cut’

Earle Ensign Dickson was born on Oct. 10, 1892 in Grandview, Tennessee, to Dr. Richard Ensign and Minnie (Hester) Dickson.

The dad was a physician from western Massachusetts; the mom hailed from Connecticut. Earle Dickson was an only child after losing his younger brother Mark in infancy, according to U.S. Census records.

An individual holds a Band-Aid box during the BAND-AID's Fashion Week Glamulance on Sept. 8, 2011, in New York City. (Kris Connor/Getty Images for Band-Aid)

The New Englanders made their way to Tennessee at some point, though Dickson lived for most of his life in Highland Park, New Jersey, where he found work at Johnson & Johnson sometime around World War I.

Despite massive advancements in battlefield medicine in the Civil War, Dickson was born into a world of primitive household bandaging — largely unchanged for centuries.

"Most people just used what they had in the house, which many times meant tying a piece of rag around the cut." — J&J historian Margaret Gurowitz

"People needing a small bandage had to make one themselves, and they were often too cumbersome to be easily applied by one person," Johnson & Johnson historian Gurowitz claims.

"Most people just used what they had in the house, which many times meant tying a piece of rag around the cut."

The medical community had in previous decades made new efforts to improve home bandage care.

Earle Dickson invented a new form adhesive bandage, now known as the Band-Aid, at his home in Highland Park, New Jersey. He was inspired to treat his wife, Josephine, who suffered from household nicks and cuts. (Illustration by Chris Hsu from "The Boo-Boos That Changed the World" by Barry Wittenstein. Used by permission of Charlesbridge. )

"In 1845 Horace H. Day patented a surgical plaster composed of natural rubber and resin coated on cloth," according to the "Encyclopedia of Modern Everyday Inventions" by David J. Cole, Eve Browning and Fred. E.H. Schroeder.

"Through the 19th century various tapes using natural (uncured) rubber were devised … None of these were aseptic or antiseptic."

MEET THE AMERICAN WHO INSPIRED THE NATION IN TWO WORLD WARS: CHRISTIAN SOLDIER SGT. ALVIN YORK

Few doctors, the authors note, were ready to adopt the germ theory pioneered by English physician Joseph Lister.

This doctor would soon lend his name to a popular antiseptic mouthwash still in use today: Listerine. Dr. Lister would also inspire the creation of one of the world’s largest companies: Johnson & Johnson.

Earle Dickson was the right man at the right time with the right product — and working for the right company.

"An American, Robert Wood Johnson, heard Lister speak in 1876 and thought of preparing a commercial line of germ-free surgical dressings," write Cole, Browning and Schroeder.

"Nine years later he formed a partnership with his two brothers and began manufacturing in New Brunswick, New Jersey, incorporating as Johnson & Johnson in 1887."

Earle Dickson was the right man at the right time with the right product — and working for the right company.

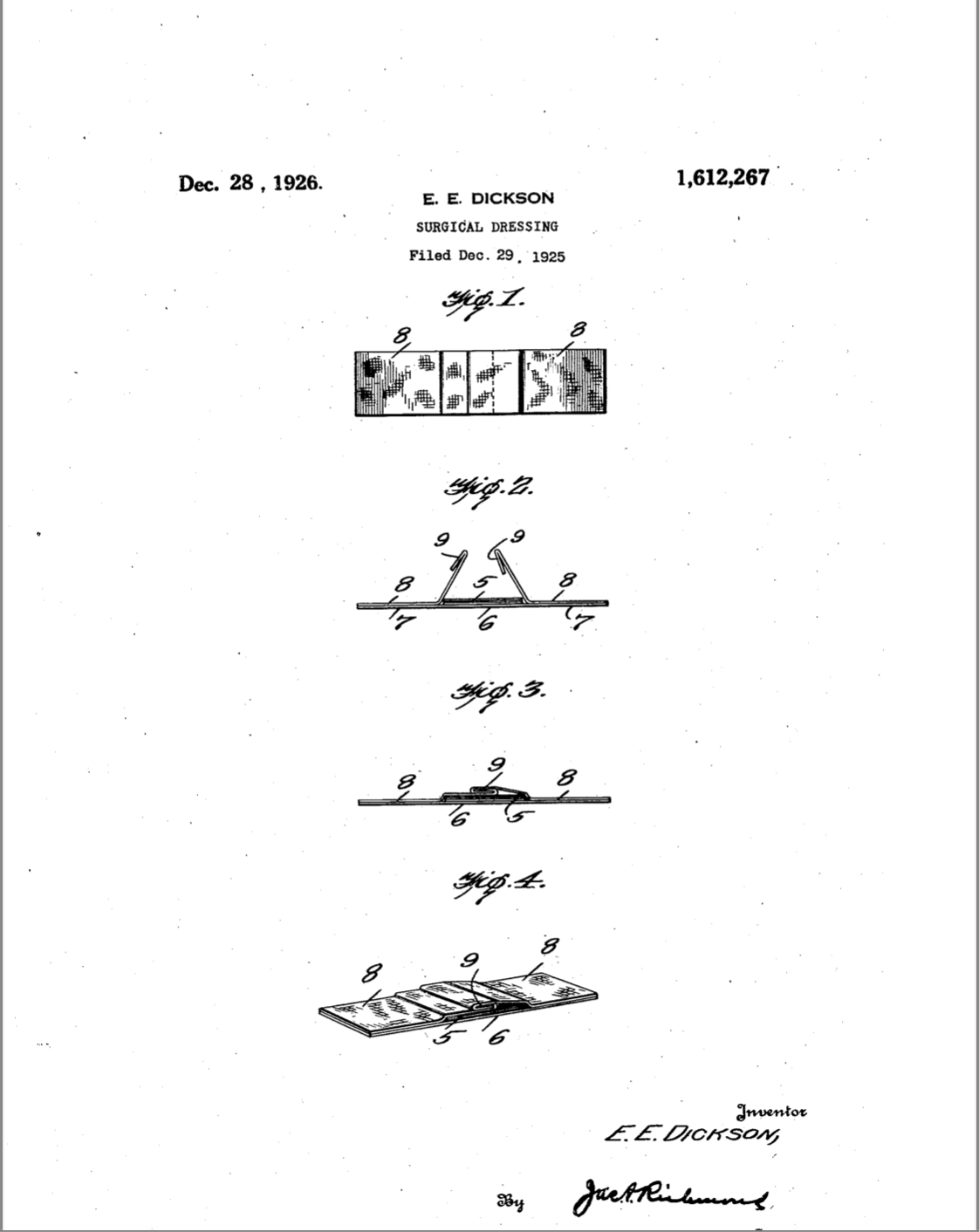

Johnson & Johnson introduced the Band-Aid in 1921. Its creator, Earle Dickson, filed a patent for his "surgical dressing" on Dec. 29, 1925, and received the patent on Dec. 28, 1926. (U.S. Patent and Trademark Office)

"Johnson & Johnson was already a popular manufacturer of large cotton and gauze bandages for hospitals and soldiers when Dickson offered up his Band-Aid solution," reports Lemelson-MIT, adding that Band-Aids first struggled to stick.

"The original handmade bandages did not sell well; only $3,000 worth of the product was sold during their first year. This may have been because the first versions of the bandages came in sections that were 2-1/2 inches wide and 18 inches long."

People had to cut off the length of bandage needed to cover the wound. It was clumsy by today's standards.

Boy Scouts frequently suffered the exact kind of injuries, minor scrapes, cuts and abrasions that Band-Aids best cured.

Improvements quickly followed. Machine-made Band-Aids of various sizes were introduced in 1924. Sterilized bandages hit the market in 1939. A sheer-vinyl version was introduced in 1958.

But it would take brilliant marketing employing America's cut and scrape-prone children to make the Band-Aid a cultural phenomenon.

America's kids embrace Band-Aids

Johnson & Johnson found an army of young American adventurers to prove their product out in the field.

They were the Boy Scouts of America. They frequently suffered the exact kind of injuries, minor scrapes, cuts and abrasions that Band-Aids best cured.

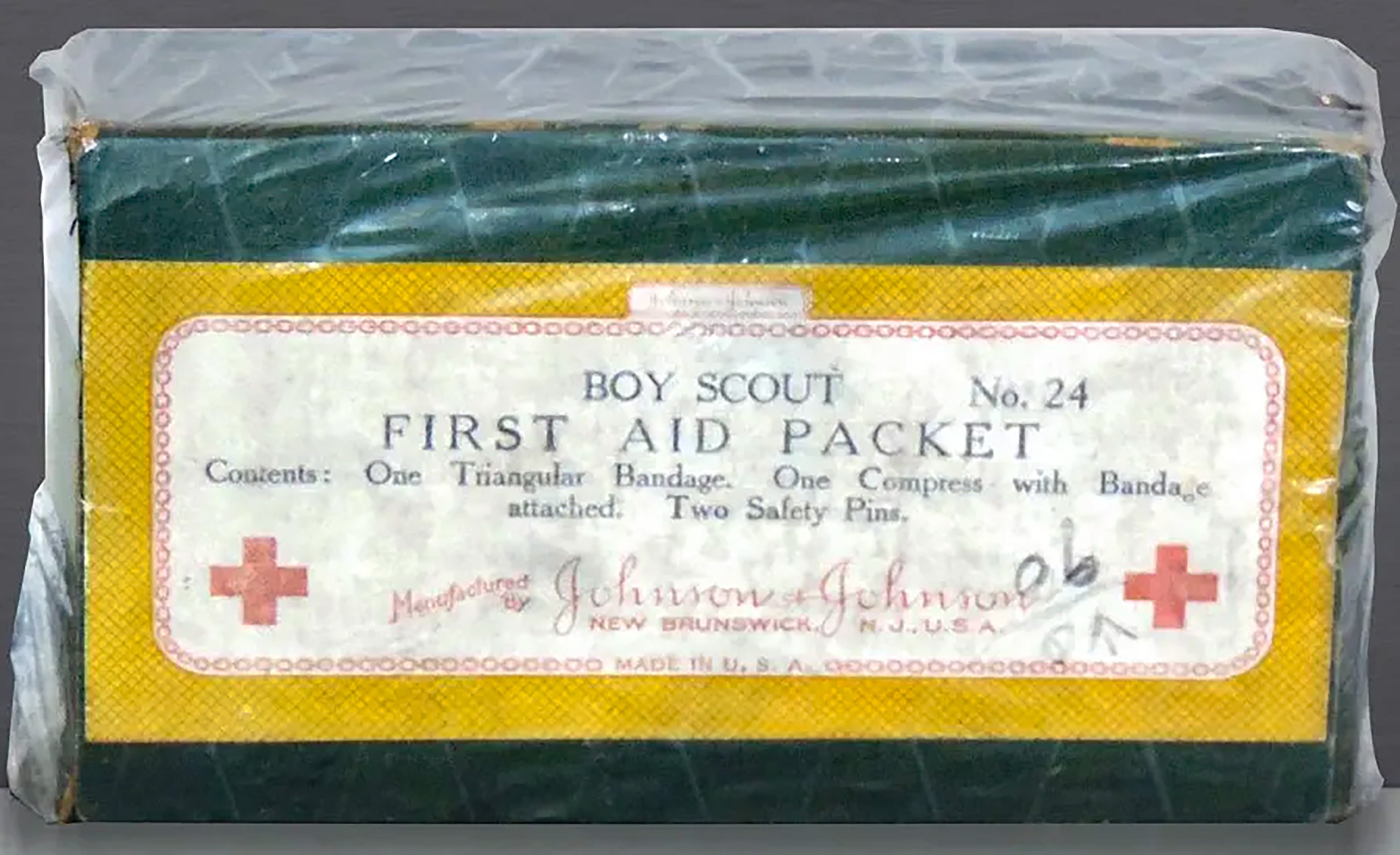

Johnson & Johnson helped popularize Band-Aids in the 1920s by sending them out in the field in first-aid kits for the Boy Scouts of America. The original 1925 "Boy Scout First Aid Packet" had a triangular bandage for a sling, a compress and two safety pins. It came in a cardboard container. (Boy Scouts of America)

"In the 1920s, the company began distributing, for free, an unlimited supply of Band-Aids to Boy Scout troops across the country," Scouting Magazine reported in 2018.

"Band-Aids also were included in the custom first-aid kits Johnson & Johnson produced for the Boy Scouts of America. The kits were designed to help Boy Scouts earn merit badges like First Aid. The original 1925 ‘Boy Scout First Aid Packet’ contained a triangular bandage for a sling, a compress and two safety pins. It came in a simple cardboard container."

Band-Aids found an international audience when they traveled overseas by the tens of millions with U.S. troops in World War II.

A more advanced Boy Scouts first-aid kit came in tin cans. The Girl Scouts were armed with Johnson & Johnson Band-Aids in 1932.

Band-Aids found an international audience when they traveled overseas by the tens of millions with U.S troops in World War II. Their service for Allied armed forces furthered the Band-Aid's visibility and popularity.

MEET THE AMERICAN WHO INVENTED THE CRASH TEST DUMMY, A LIFE-SAVING INNOVATION

Band-Aids became a part of bedtime reading after the war, in one of the most successful children’s books in U.S. history.

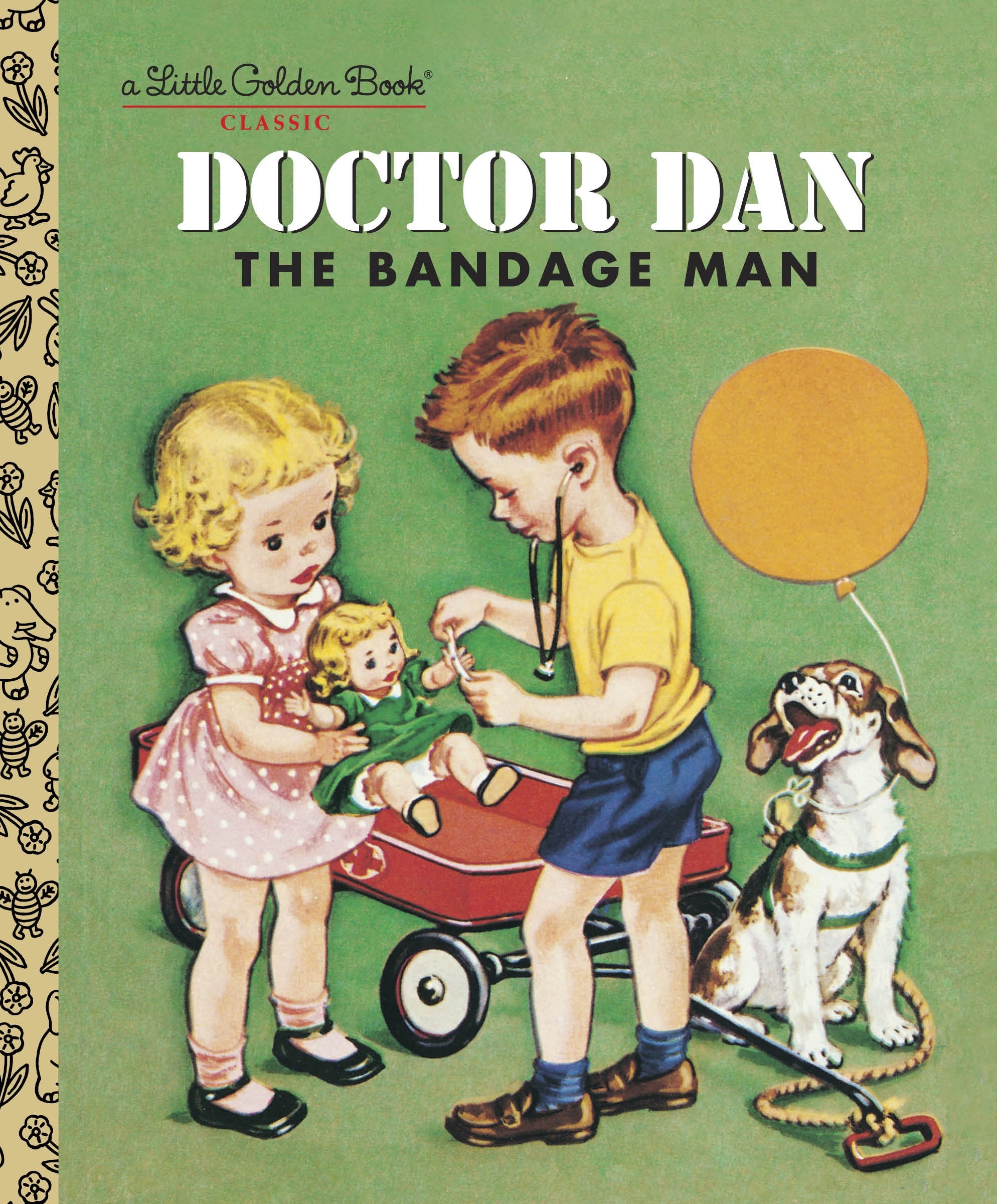

"Doctor Dan the Bandage Man," from Little Golden Books in 1950, tells the tale of a boy named Dan whose "boo-boo" is bettered by a mom when she applies a Band-Aid to his finger.

Transformed by the healing powers of the Band-Aid, Dan spends the rest of the book wheeling the bandages around in his wagon healing neighborhood pals, pets and even toys.

"Doctor Dan the Bandage Man" was published by Little Golden Books in 1950. It featured a boy named Dan who treated local children, pets and toys with Band-Aids. The book came with six Band-Aids and sold millions of copies — helping to popularize the Johnson & Johnson product. (Penguin Random House)

"The book came with six real Band-Aid Brand Adhesive Bandages — attached inside and advertised on the cover — so that kids could bandage their own hurt toys, should the need arise," Gurowitz writes.

The publisher printed 1.75 million copies of the book in its first edition alone — putting a total of 10.5 million Band-Aids in the hands of American boys and girls.

Dickson’s Band-Aid had already proven itself perhaps the most successful home care product in history. Now it entered the realm of pop-culture icon.

The book was added to the Smithsonian collection at the National Museum of American History, which recognizes the book for its "innovative" display and marketing techniques.

"Simon and Schuster paired with Johnson & Johnson to promote the latter’s brand-name ‘Band-Aids’ and targeted one of its likeliest consumers, children," the museum notes.

Johnson & Johnson helped popularize Band-Aids by packing them in first-aid kits for Boy Scouts. After an initial kit came in a simple cardboard box, Johnson & Johnson debuted an upgraded BSA first-aid kit in a tin box. Inside, scouts found burn and antibiotic creams, first-aid instructions and several kinds of bandages, including Band-Aids. (Boy Scouts of America)

"Boys and girls would sport Band-Aids in colorful shapes of stars, hearts, circles and flowers from samples included in the pages of the book, all the while learning the basics of first aid."

Dickson’s Band-Aid had already proven itself perhaps the most successful home care product in history. Now it entered the realm of pop-culture icon.

The Band-Aid Bench

Earle Dickson died in Ontario, Canada, on Sept. 21, 1961. He was 68 years old.

After his breakthrough contribution to the company, Dickson spent the rest of his professional career working for Johnson & Johnson.

Earle Dickson was born in Tennessee on Oct. 10, 1892. A cotton buyer for Johnson & Johnson, he invented the Band-Aid in his Highland Park, New Jersey, home in 1921. Dickson died in Kitchener, Ontario, on Sept. 21, 1961. (Courtesy Johnson & Johnson)

"Johnson & Johnson eventually made Dickson a vice president at the company, a position in which he remained until his retirement in 1957," writes MIT-Lemelson.

"He was also a member of the board of directors until his death in 1961. At the time of his death, Johnson & Johnson was selling over $30,000,000 worth of Band-Aids each year."

MEET THE AMERICAN WHO INVENTED THE CRASH TEST DUMMY, A LIFE-SAVING INNOVATION

The success of Dickson's product is hard to fathom.

Johnson & Johnson today produces 10 million Band-Aids every day — about 117 bandages each second.

Yet Band-Aids have gone far beyond just a "product." They're part of the wider cultural lexicon.

Band-Aid inventor Earle Dickson lived in Highland Park, New Jersey. The community installed a Band-Aid bench on South Fourth Avenue in 2019 in Dickson's honor. Local artist JoAnn Boscarino created it. (Highland Park Arts Commission)

"Put a Band-Aid on it" or "Band-Aid solution" are common refrains to describe a short-term fix to a problem.

The British charity ensemble group Band Aid formed in the 1980s to give the world the holiday classic "Do They Know It’s Christmas." Band Aid inspired Live Aid, the international pop-culture sensation charity concert of 1985.

Johnson & Johnson today produces 10 million Band-Aids every day — about 117 bandages every second.

The Band-Aids were the name given to the rock-and-roll groupies by writer/producer Cameron Crowe in the movie and stage versions of "Almost Famous."

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR LIFESTYLE NEWSLETTER

Highland Park, New Jersey, celebrated its hometown medical-inventor hero in 2019, introducing a memorial to Dickson known locally as the "Band-Aid bench." Local artist JoAnn Boscarino designed it.

It sits on South Fourth Avenue, about two blocks from the Dicksons' former home on Montgomery Avenue.

"We’re really proud that Highland Park is known as the birthplace of the Band-Aid," town councilman Matthew Hersh told Fox News Digital.

The new Band Aid 20 CD single "Do They Know It's Christmas," at HMV in London's Oxford Street. (Peter Jordan - PA Images/PA Images via Getty Images)

"It fits perfectly with our legacy of health care innovation."

Highland Park, he noted, has spawned other great contributions to the world of science and health care.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

The community was home to Selman Waksman, who won the 1952 Nobel Prize in Medicine for discovering antibodies to battle tuberculosis; and Arno Allen Penzias, who won the 1978 Nobel Prize in Physics for research that helped establish the Big Bang Theory.

"We're proud of Highland Park's history as a witness to innovation in health care and progress," Hersh said. "We're proud of Earle Dickson."

To read more stories in this unique "Meet the American Who…" series from Fox News Digital, click here.